Documenta,

Jun 16, 2007 - Sep 23, 2007

Kassel, Germany

Documenta 12

by Kirsten Einfeldt

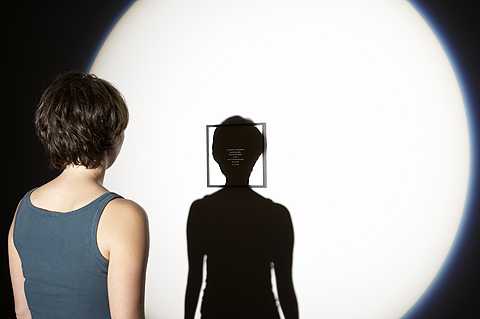

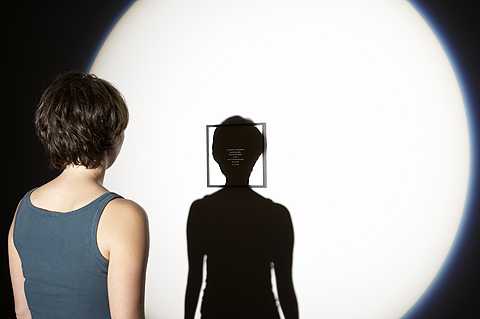

At the Aue-Pavillon, whose architecture speaks of the origin of Documenta within the context of the Federal German Garden Exhibition in Kassel, the works were hard to appreciate, and this was exacerbated by the lack of light and setting. This seriously hampered the perception of well-conceived, sensitive works like the laconic orchestra of electric guitars, Black Chords plays Lyrics (2007) by the Frenchman Saadane Afif (1970), the installations of 1001 Quing-dynasty (1644-1911) chairs in groups by Ai Weiwei, Trisha Brown’s Roof and Fire Piece (1973), and the English photographer Jo Spence’s (1934-1992) series, Remodeling Photo History (1982), on the different concepts of femininity. Moreover, the discourse of abstraction as "liberation of form and therefore of spirit", in the tradition of the artistic director of the first Documenta, Arnold Bode, became tiresome due to its repetition in the different exhibition areas, as was the case with McCracken’s sculptures, on display at the Fridericianum Museum, the Aue-Pavillon and the Neue Galerie alike. And it was not merely Latin American visitors who realized that Latin, and non-European in general, participation in Documenta 12 was scant: the politically committed work of the members of the Argentinean movement of the sixties, Tucumán Arde (Tucumán Is Burning) , Graciela Carnevale (1942; Untitled, 1968) and León Ferrari (1920; Pasarelas,1981); the installation criticizing the viewer’s relationship with art in Eclipsis (2007) by the Chilean Gonzalo Díaz (1947) and Escultura Negra (Black Sculpture) by Brazilian artist Luis Sacilotto (1924-2003) as examples of specifically South American art were among the few Latin American pieces on display.

The way the Fridericianum and Wilhelmshöhe rooms were set out, and Buergel’s curatorial focus "on the crisis in form" spoke of two strong references to the theme of this Documenta: the Viennese formalist discourse of the late nineteenth century, and the aforementioned first Documentas of 1955 and 1959. Museographically, the installation Where We Were Then, Where We Are Now (2007) by the German Simon Wachsmuth (1964), a historic section featuring objects and documentary films of the ancient royal city of Persepolis on walls painted in slightly altered classical colors, made reference to forms of display that were common during the nineteenth century, like the Ancient Masters rooms in Berlin’s recently reopened Bode-Museum or those of Vienna’s Kunsthistoriches Museum. Whereas Arnold Bode displayed the avant-garde works banned by the Nazi regime, which had fallen just ten years before, and subsequently contemporary avant-garde works in rooms severely damaged during the Second World War, Buergel’s return to nineteenth-century museum aesthetics was of a key importance. The heritage of Viennese formalism was highlighted. "Kunstwollen", the term coined by the Austrian art historian Alois Riegl (1858-1905) to explain the impulse to create art, along with the so-called "geometric art" of the primitives, which for decades determined the discourses on the origins of abstraction in European avant-garde circles, is one of the bases for stating a "crisis of form" today (3). Riegl distanced himself from the theory put forward by the German architect Gottfried Semper (1803-1879), that the origin of "geometric art" lay in the need to create primary forms in the textile arts as the first kind of human protection which would later lead to architecture (4), and saw the origin of art in universal human spontaneity (5). When Buergel speaks of the "migration of form", he refers to the Rieglian definition of form, which traces its development according to its historical, political, social and cultural context, from fourteenth-century Persian art to the present. This ambitious approach is legitimate and extremely interesting, particularly bearing in mind today’s processes of globalization. Nonetheless, Documenta 12 lacked a central explanatory essay by its artistic director to provide full information on the curatorial concept, in the same way that there was a lack of explanatory texts in exhibition areas, making the exhibition cryptic for viewers to understand.

Some extraordinary works - the confrontation of political fundamentalists through artistic processes by the Polish artist Artur Zmijewski (1966; Them, 2007), the literally migratory form of the work-in-progress Would you like to participate in an artistic experience? (1994-2007) by the Brazilian Ricardo Basbaum (1967), and Ai Weiwei’s 1001 Chinese visitors in Kassel, which questioned established orders between "the known" and the "unknown" (Fairytale) stood out in a wide-ranging and highly uneven exhibition. In terms of the way the concept was realized, however, in comparison with previous Documentas such as the tenth, and the critical review of contemporary artistic production of 1997 directed by Catherine David, Documenta 12 failed to live up to what could have been a revealing proposal.

Kirsten Einfeldt

NOTES:

1) " Die Ausstellung ist vor allem Ausstellung, also kein Wissenspaket, das uns mehr oder weniger akademisch çber lokale Zusammenhçnge informiert. Denn beschreitet man diesen Weg, degradiert man Kunst zur Illustration." Roger M. Buergel: Die documenta 12 setzt auf die Migration der Form, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, April 21 2007, Nr. 93, p. 48.

2) See Roger M. Buergel: Die documenta 12 setzt auf die Migration der Form, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, April 21 2007, Nr. 93, p. 48.

3) See Alois Riegl: Spätrömische Kunstindustrie, Vienna, 1901.

4) See Gottfried Semper (1860-1863): Der Stil in den technischen und tektonischen Künsten oder praktische Ästhetik, 2 volumes, volume I: Die textile Kunst, edited by Friedrich Piel, Mittenwald 1977.

5) See Alois Riegl (1893): Stilfragen. Grundlegungen zu einer Geschichte der Ornamentik, edited by Friedrich Piel, Mittenwald 1977, pp. 1-32, particularly p. 4.

|