Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofia,

Oct 26, 2012 - Mar 11, 2013

Madrid, Spain

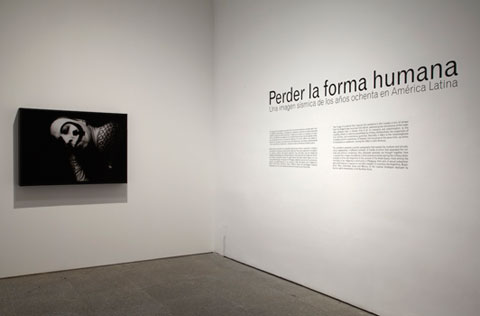

Losing the human form. A seismic image of the 1980s in Latin America

by Francisco Godoy

Above all, there aren’t any corpses After a long period of research, the Red de Conceptualismos del Sur is presenting its first major exhibition in Madrid, this time with Ana Longoni, Jaime Vindel, Fernanda Carvajal, Miguel López, Mabel Tapia, André Mesquita and Fernanda Nogueira as coordinators, in addition to the work of another 18 researchers from the Red. Founded at a meeting in Barcelona in 2007, the Red was formed to unite Latin American and Spanish researchers and artists "in the need to intervene politically in the neutralizing processes of the critical potential of a set of ‘conceptual practices’ that took place in Latin America during the sixties".(1) After delimiting the period of their research framework, the findings of the artists and researchers led them to investigate other periods as well. The eighties turned out to be a decade in which what had taken place in the 60s and 70s came together and blew up into a series of practices where individual and collective bodies crossed, collided and even got lost in the tangle of complex relations they established with different political situations. Hence the birth of the Perder la forma humana. Una imagen sísmica de los años ochenta en América Latina (Losing the human form: a seismic image of the 1980s in Latin America) exhibition, which has been developing through collective research that was gradually woven into different public and private encounters, the most significant being Poner el cuerpo. Formas de activismo artístico en América Latina, años 80 (Placing the body: forms of art activism in Latin America during the eighties), held at the Centro Cultural de España in Lima, Peru, in July 2011. Highly fragmented, but organized by "affinities and contagions", the exhibition takes up a third of the third floor of the museum and by and large seeks to establish a "counterpoint between the highly intimidating effects of violence on bodies, and the radical experiences of freedom and transformation that challenged the repressive order".(2) Inversely paraphrasing Nestor Perlongher(3), one could say that Perder la forma humana is an exhibition in which "there are no corpses", because they have all come back to life, ranging from an early tomb of Pignochet made in Recife by the Equipo Bruscky & Santiago, to the silhouettes of those arrested and missing in Argentina, to Elías Adasme’s hanging body, who likens his own image to that of Chile experiencing the ravages of the dictatorship. The great majority of the artwork exhibited consisted of "corpses" buried within artists’ archives, never catalogued and even forgotten altogether due to their disruptive effect on the canon of art production, which they are "reviving" here. In general they are reproducible objects for mass distribution and public intervention that were presented as part of the political and cultural processes that had little to do with the dynamics of precarious local art markets. In fact they took root infields removed from those understood as "visual arts": poetry, architecture, punk posters, political posters, music or theater. This is where the exhibition’s greatest strengths lie: in questioning the canon of what is considered to be art and recovering projects of poetic-political intensity and collectivism in times where individualism and capitalism were being radically promoted in countries like Argentina, Chile, Peru and Brazil, doubtless those with the greatest presence at the exhibition. Those strengths also reveal one of its strongest flaws: these works are not linked to different discourses and productions of visual art that, while using other approaches, also sought to shape their own ways of dealing with "states of catastrophe", the absence of which certainly leaves an interpretative gap on that period for the Spanish public. Where the dead wander: in corridors Although the title of the exhibition indicates that the project centers on the 80s, the works on display date from 1973, with Pinochet’s coup d’état in Chile acting as the starting point. (4) This is also the beginning of an exhibition that shows no qualms in repeating the works of artists in different sections, or of presenting "art" productions together with others normally pertaining to the documentary fieldin the same space. The exhibition greets the visitor by linking the political demand for democracy to the construction of a "dissident subject" designated by its difference from what has been construed as normal. This room features a portrait of Pedro Lemebel with the sickle and hammer on his face --as a sort of militant makeup-- that, along with his high heels, was the costume with which he read his I speak for my difference manifesto at a leftist political gathering in Santiago in 1986, the audio of which can be heard next to the image.

A jumbled, redundant montage of black and white photographs and etchings leads to the next room. This is where one of the exhibition’s three axes begins; titled Hacer política con nada (Making politics with nothing); it focuses on the strategic visuality of social movements to fight dictatorships using other means than straightforward militancy, particularly in Argentina and Chile. In addition to the artworks on the walls, the room features a projection on the floor of a silhouette – referring to the Argentinean Siluetazo— by Dalmiro Flores that one can step on, thus demystifyinga creative process using the barest resources and letting the viewer take part in it. This "spatial" curatorial strategy is repeated in the next room, which contains photographs by Paz Errázuriz of the performance La conquista de América (The Conquest of America) in which Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis (The Mares of the Apocalypse) danced barefoot on a map of Latin America strewn with shards of glass. The map is reproduced in the room, with the pieces of glass but minus the blood. Perhaps this strategy –reconstructing objects pertaining to the memory of bodies in action- is one of the exhibition’s weakest points, as is the case with Tu dolor dice: minado (Your pain says: mined) by the same collective, or Pinochet’s aforementioned tomb, which, in the projection and photographs accompanying the "object", one can clearly see the intensity of the public performance. This axis ends with works by the collectives Taller NN and EPS Huayco, Agrupación de Plásticos Jóvenes and Artistas del MAS, among others.

|